Monday, August 4, 2025

A Normal Guy's Perspective on Linux

Monday, January 1, 2024

Star Trek: Picard Season Three—The TNG Finale Band-Aid

- Do something Internet related, with a website and stuff.

- ???

- Profit!

Thursday, June 15, 2023

Enough With the Canon Fundamentalists

Thursday, June 8, 2023

Weird Star Trek: Star Trek Novelverse Edition

And yet, during its first 20 years the Star Trek universe was a pretty wide-open place. The original series and the first few movies didn't really do any deep dives into alien cultures, the character's pasts, or Federation politics. So all that stuff was open for exploration, and novels were the perfect place to do it. Unlike TV or movies, a book's only limits are the author's imagination and what the editors will let them do. And up until 1988 or so the editors mostly let Star Trek novel authors indulge themselves. The result was glorious run of deeply weird, occasionally wonderful stories full of stuff that was totally inconsistent with where the Star Trek universe ended up going. For example:

Of course, the whole thing turns out to be a Klingon ploy to trick Kirk into helping them take an invasion fleet past Federation defenses. And the peaceful Klingons only act that way because they've been taking drugs to suppress their violent tendencies. When they go off the drugs, they devolve into snarling, animalistic monsters. To be fair, a formerly drugged Klingon who's reverted to her violent tendencies does have a moment of compassion for Kirk after he collapses from injuries he sustained earlier in the story. But the overall message--that Klingons are inherently violent and animalistic--very uncomfortably mirrors stuff that real-world racists say to justify the terrible things they do.

I believe that this was one of the last books (maybe the last) published before Gene Roddenberry's office--in the person of his manservant Richard Arnold--took a direct role in approving novel manuscripts. And let me be clear: I never liked the late Richard Arnold. He was a fundamentalist who thought the only person allowed to have original Star Trek ideas was Gene Roddenberry. He loved to tell behind-the-scenes stories, and all of them were about a time when he was right about a piece of Star Trek trivia and some more important or famous person was wrong. If he was a Star Trek character, he'd be one of the hooded Lawgivers from "The Return of the Archons" who mindlessly enforced the will of the Landru computer.

That being said, I imagine Richard Arnold probably would have rejected this book, and it would've been the one and only decision of his that I agreed with.

The Forgotten TV Western That's Part of the Star Trek Universe

Timetrap was not the first novel where a main character disappeared on a Klingon-related mission. In 1985 Pocket released Ishmael by Barbara Hambly. It's one of the first Star Trek novels I remember seeing in my local Waldenbooks, maybe because of how strange the cover art was:

It clearly said "Star Trek", and that was obviously Mr. Spock there on the right. But who were those other people and why were they all dressed like riverboat gamblers? Whatever explanation you can think of, the truth is way weirder.

The 1968-69 TV season was Star Trek's last on NBC. Meanwhile, over on ABC a new comedy-Western series called Here Come The Brides was starting the first of what would be a two-season run. The premise of the show revolved around women who came to Seattle after the Civil War to find husbands. One of the show's characters, sawmill owner Aaron Stemple, was played by Mark Lenard (the same guy who played Spock's father Sarek a year earlier). In the book, Stemple finds an amnesiac Spock unconscious in the woods and takes him to his cabin to recover. As we go along, Spock meets the show's other characters and becomes integrated into their social circle, making this book basically a Star Trek/Here Come The Brides crossover.

Eventually we learn that Spock got caught up in a Klingon plot to travel back to the 1860s and kill Aaron Stemple to prevent him from helping to thwart Earth's takeover by the Karsid Empire. Of course they fail, Spock gets his memory back, and we learn that Aaron Stemple is actually one of his human ancestors. Oh, and there's also a scene in an alien cantina where Dr. Who, Han Solo, and Apollo and Starbuck (the Richard Hatch and Dirk Benedict versions) all hang out together.

A book like this would probably never get published today and it's absolutely glorious.

The Klingon Empire Gets Canceled By Godlike Aliens

When Spock Must Die! was published in January 1970, Star Trek had been off the air for less than a year. The show was dead and buried as far as anyone knew, and author James Blish was free to do whatever the heck he wanted.

So he wiped out the Klingon Empire.

The book is a semi-sequel to the episode "Errand of Mercy", where the practically-omnipotent Organians stop a Federation-Klingon war and force the two sides to sign a peace treaty. In Spock Must Die!, the Klingons imprison the Organians on their planet with a powerful force field, which leaves the Klingons free to make war on the Federation. Eventually the Enterprise crew takes down the forcefield and frees the Organians, who respond by taking away the Klingons' spaceflight ability for 1,000 years. Imagine what future Star Treks would have been like if the Klingons were completely taken off the table.

Saturday, May 7, 2022

The Star Trek: Picard Dumpster Flambé

- Mr. Breen sincerely believes that he makes movies to communicate the Big Important Ideas in his brain.

- None of his ideas are all that big or important, and he is not very good at using the medium of film to communicate them.

Tuesday, January 25, 2022

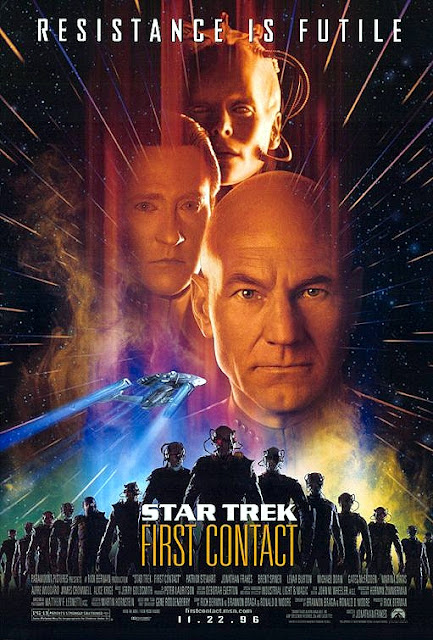

The First Contact Retrospective

Sometimes I wonder how the people who are always complaining that Discovery isn't "real" Star Trek would react to a big-screen reboot of The Next Generation that reimagined that era's starship Enterprise as a warship captained by a grim, revenge-obsessed Captain Picard. What if it was more darkly violent than any previous Trek film, and relegated the optimistic Roddenberrian message to a paper-thin B-plot? If that ever happened, I'll bet the online Star Trek Fundamentalists would throw a massive Internet tantrum that would make the furor over The Last Jedi look like a polite disagreement.

Oh wait, that happened in 1996 and they loved it:

The 1990s were a weird time. We had a movie where the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles danced with Vanilla Ice. Pauly Shore had a career. And amazingly, against all reason, we had a dark and gritty Star Trek: The Next Generation reboot that the very same fans who now rail against modern Trek for being too dark and violent absolutely loved. How did this happen?

It's worth remembering that the original show was made during the Vietnam War by World War II and Korean War veterans, in a world that lived under the constant threat of Mutually Assured Destruction. The idea that conflicts should be solved with words instead of weapons was a somewhat-radical notion that greatly appealed to the show's young audience, most of whom were personally affected by Vietnam in one way or another.

|

| Granted, he went back to his old self two pages later, but for the majority of that issue he was wearing black and toting a ridiculous amount of guns |

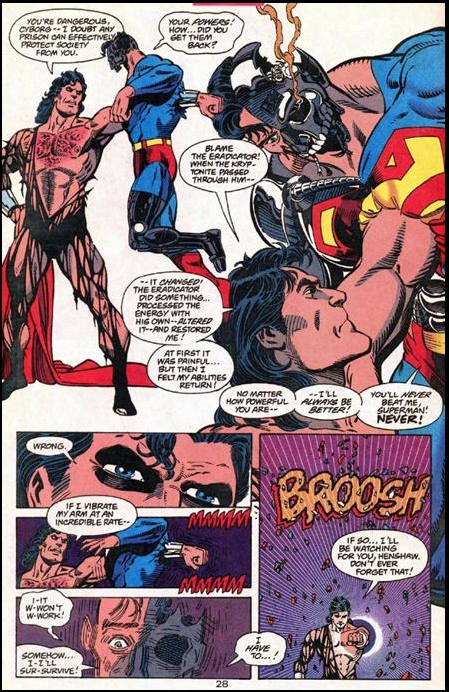

What I'm trying to say was that the young Star Trek audience in 1996 wasn't a bunch of socially-conscious peaceniks. We were stupid adolescents who saw violence as empowering and fun, but we had zero understanding of its real-world consequences. As much as we enjoyed Star Trek: The Next Generation, we tended to think of Captain Picard as kind of a boring wimp who talked too much:

|

| From a 1994 issue of Starlog |

So when the first stills from the movie showed up in Star Trek Communicator magazine, featuring scenes like this one with an action-oriented Picard leading a security team with beefy phaser rifles down a darkened corridor, we were stoked:

And when we saw a sweaty, rage-filled Captain snarl that "the line must be drawn here!" in every trailer and TV spot (along with shots of the biggest space battle in Star Trek history up to that point) we totally lost our minds.